Screening and Assessment Tools

What’s next when you suspect neurodivergence?

20 MINUTE READ

Published September 2024

AUTHOR

Rachel Oppenheimer, PysD

Contributing Editor, Licensed Psychologist

If you have noticed that your child is developing differently than their peers, or you have concerns about their development, you may be wondering “What do I do now?” There are many different pathways to start to examine a child’s development, and it can be a confusing and somewhat counterintuitive path. Having a good understanding of what the professionals are looking for, and how they are gathering that information can help you maximize your time in a doctor or psychologist's office.

Why do I even want a formal diagnosis for my child?

As our understanding of development has increased, we have also increased our understanding of developmental differences. The term neurodiversity is an alternative to disability or diagnosis - it is a term applicable to developmental differences and/or executive functioning differences. Basically, any brain that may be “wired differently” or learning differently can be considered neurodiverse. The neurodiversity movement is all about accommodating and supporting the many different learning and processing styles, and embracing the differences in how we all see the world. It can feel counterintuitive to have this inclusive philosophy while also looking for a professional to diagnose and treat your child.

However, a thorough and comprehensive evaluation can be an essential tool for determining what supports are most beneficial, establishing treatment goals, helping to make school decisions, and balancing supports and interventions for your child. A formal diagnosis can help set expectations, establish a baseline of strengths and areas to target in interventions, and opens doors to access services that can help your child make developmental gains.An early diagnosis of any type of neurodiversity or developmental difference means accessing early intervention (see Early Intervention guide for the research on improved developmental outcomes), as well as accessing the appropriate supports, resources, programs etc that will increase your child’s ability to cope, reduce parental stress, and ultimately lead to increased adult independence¹.

Breaking it down further

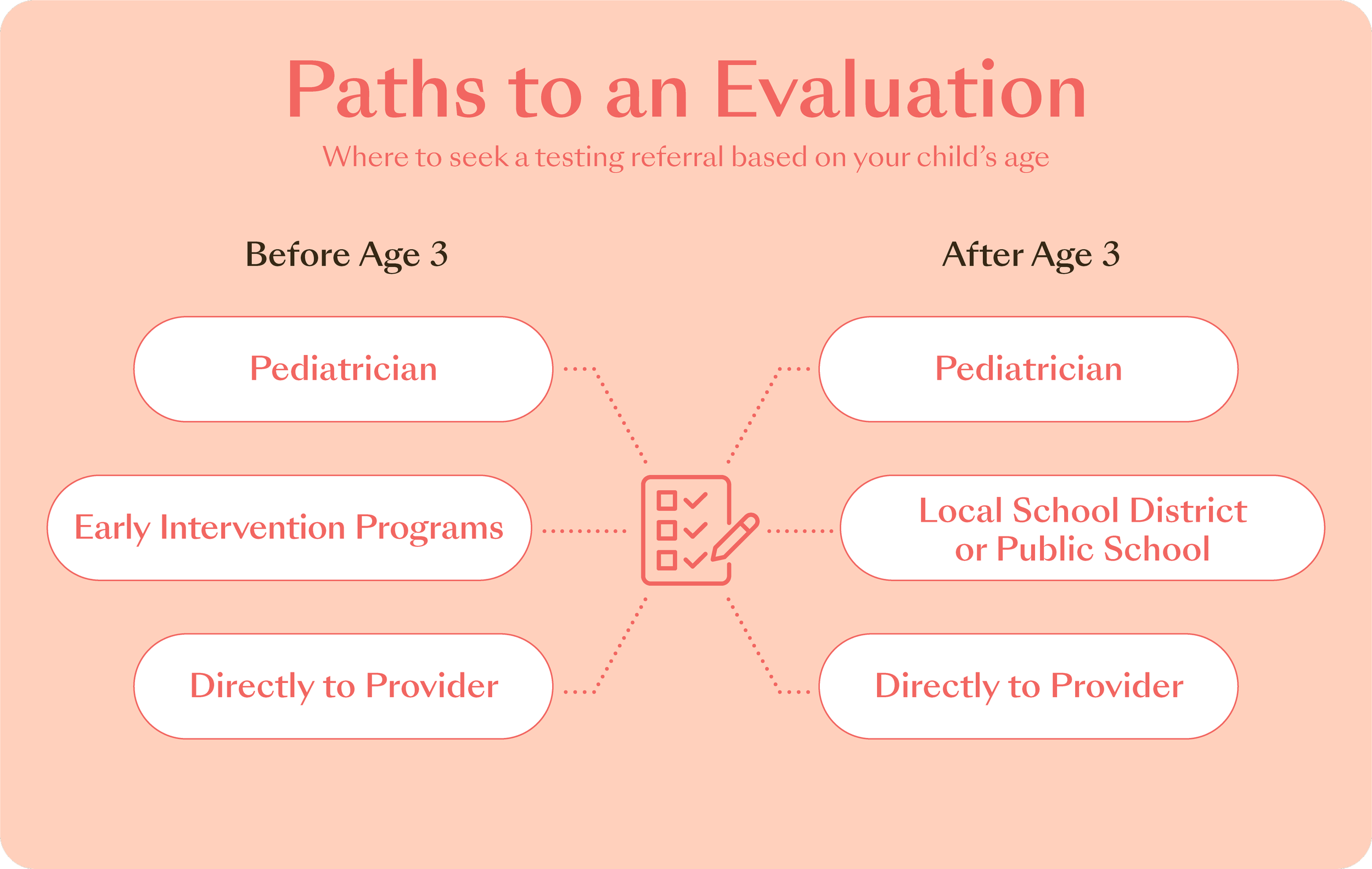

There are several different paths to a diagnosis - and even several different types of diagnoses. There is not necessarily a “Start Here” approach because concerns can come from sources such as you as the parent, the pediatrician, the daycare or preschool - or all of the above! Collaboration and input from multiple sources are a key facet of understanding if a child has a diagnosable condition.

Provider inputs

There is not a sole test, nor are there any biological markers (brain scans, blood tests) that can diagnose Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Because these diagnoses impact development, extensive developmental history will be taken - from as far back as pregnancy, if this information is available. In addition, parents and caregivers will be asked to complete checklist forms on behavioral, social, emotional, and developmental information. The provider may request to observe your child, especially if they are in a daycare or preschool environment - seeing how a child interacts with peers can be a valuable piece of information for a diagnostic provider. Diagnostic providers may also ask for multiple raters, looking to gather a consensus of information about behaviors and interactions. This may mean asking both parents, grandparents, nannies or au pairs, or daycare providers. If your child is already in therapy or getting early intervention services, those records will be requested, and that therapy provider may also be asked to provide information.

With so much variability in the realm of neurodivergence, it takes a specialist to properly identify and diagnose something like ASD or ADHD. A developmental pediatrician or clinical psychologist are the best professionals qualified to make these diagnoses. For genetic disorders, such as Down Syndrome, physical markers plus a genetic test makes for a diagnosis - you may even know about some genetic differences before your baby is born. Learning disorders are best diagnosed by an educational diagnostician or clinical psychologist - and there is a required amount of academic exposure before a learning difference can be identified.

Because so many domains are impacted by neurodivergence, there is a growing push to ensure that a diagnosis of a developmental disorder has an interdisciplinary, or multidisciplinary approach². This should include a speech and language pathologist, as communication differences are a hallmark of neurodivergence. Other providers included on the team may include an occupational therapist, to evaluate physical and sensory differences, a psychologist specializing in child development, a pediatrician or psychiatrist, and / or a neurologist.

The gold-standard for an ASD diagnosis is the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) in combination with a detailed and structured clinical interview with caregivers³. Likely other formal measures will be included as well. The ADOS-2 is an activity based assessment that requires extensive training to look for the subtleties of communication, social, and behavioral differences in an individual with ASD. It is observation based, so your child will be played with and observed (typically with you in the room, if your child is not yet talking, or is younger than age 5 or 6), and these qualitative observations are then rated.

Because autism is typically diagnosed via observation and clinical interview, medical professionals who don’t provide formal testing can provide an official diagnosis of autism - this may include your pediatrician, a psychiatrist, or a neurologist. However, because the ADOS-2 is the “gold-standard,” and has so much evidence to support its accurate ability to detect autism spectrum disorder, many care providers and insurance companies won’t recognize a diagnosis of ASD without having an ADOS-2 as a part of the diagnostic process⁴.

Something like ADHD is typically diagnosed using similar rating forms and a parent interview, and may also include observation of the child. A requirement of ADHD is the behaviors in at least two settings, so providers will want to know if your child looks different in the home versus at preschool. Or, if there is a difference in structured time or unstructured time. A performance test - this looks at how well your child can focus, switch attention, and maintain attention when bored - may also be included. The evaluator will likely want to look at your child’s problem solving and emerging academic abilities, as sometimes early learning differences can look like ADHD based solely on symptomatology.

Education system inputs

The Individuals with Disability Education Act (IDEA) is federal law that specifies that all children are entitled to a free, fair, and appropriate public education⁵. IDEA specifies that supports, accommodations, and modifications are required for children with a disability to access said public education - those supports are what is known as special education. Children ages 3 and older are eligible for school support if they have a diagnosis that makes them eligible for special education supports. IDEA law says that a child with disabilities has the right to the individualized and tailored services and support they need to be able to access the same educational opportunities as their neurotypical peers. It is not easy to navigate the system though, and there will need to be collaboration between you as a parent, your child’s medical providers, and the school system to fully access the benefits of IDEA.

However, it isn’t enough to bring a diagnosis from your pediatrician to the local school. The school district will want to do their own evaluation looking at all domains of a child’s life - social, emotional, behavioral, and academic. The school may also want to look at speech and language, occupational therapy needs (such as sensory supports) - they may also look at physical therapy, or adaptive technology - this individualized assessment will provide the school district with the information needed to make an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). An IEP is the guiding document that will be tailored, modified, amended and updated to suit your individual child’s needs within the school environment. The school district is required to provide the least restrictive environment (LRE), meaning that to the maximum possible, a child with an identified disability or educational eligibility will be learning with his or her peers.

A school cannot provide a medical diagnosis, however. After their evaluation to determine the IEP, they may provide labels/eligibility, and one such label may be autism - but if they suspect attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, they may provide the eligibility of “Other Health Impaired” and request a medical diagnosis to support said eligibility. Other eligibilities from an educational perspective include vision impairment, hearing impairment, emotional disturbance, intellectual disabilities, orthopedic impairment, speech impairment, etc. For very young children who do need early intervention services (see Early Intervention guide) but do not yet qualify for an eligibility or diagnosis, there is a “non-categorical early childhood” eligibility that can still ensure services.

Because autism is typically diagnosed via observation and clinical interview, medical professionals who don’t provide formal testing can provide an official diagnosis of autism - this may include your pediatrician, a psychiatrist, or a neurologist. However, because the ADOS-2 is the “gold-standard,” and has so much evidence to support its accurate ability to detect autism spectrum disorder, many care providers and insurance companies won’t recognize a diagnosis of ASD without having an ADOS-2 as a part of the diagnostic process⁴.

Something like ADHD is typically diagnosed using similar rating forms and a parent interview, and may also include observation of the child. A requirement of ADHD is the behaviors in at least two settings, so providers will want to know if your child looks different in the home versus at preschool. Or, if there is a difference in structured time or unstructured time. A performance test - this looks at how well your child can focus, switch attention, and maintain attention when bored - may also be included. The evaluator will likely want to look at your child’s problem solving and emerging academic abilities, as sometimes early learning differences can look like ADHD based solely on symptomatology.

What the research says

A formal diagnosis reduces stigma, and decreases barriers to care and services⁶.

A trained diagnostic provider will choose the methods and assessment tools that are most sensitive and accurate to your specific concerns for your child⁷,⁸.

Children with developmental differences who are diagnosed as early as possible (such as before school age) access more interventions, and have better overall cognitive and verbal skills, and require less ongoing support than children who were diagnosed later⁹.

How to access an evaluation

There are many paths to a diagnosis outcome which are age and situation dependent. Many times parents bring their concerns to providers directly, or to their pediatrician who refers to providers. Other times it may be the school or daycare provider who voices concern - they have more children, or more data, to compare your child to. Sometimes it is the pediatrician, who has been monitoring development during regular visits, and feels that it's time to formally assess.

Before Age Three

For many families, the first step for an evaluation is to discuss concerns with your established pediatrician, who will offer referrals. Prior to age 3, they may steer you down an early intervention route, which does not necessarily mean a formal diagnosis - early intervention serves as a potential prevention of some diagnoses, such as language disorders, if intervened early enough. If, prior to age 3 and during early intervention, an evaluation is warranted to access additional services and to start long term planning, that interventionist may recommend you for an evaluation. Alternatively, you may wish to look at your insurance provider list, or even an internet search for a developmental diagnostic provider. You want to specifically look for a clinical psychologist with experience evaluating in the early childhood period, or a developmental pediatrician.

After Age Three

If your child is over the age of 3, you can also reach out to your local public school district. Expressing your concerns, you can then ask for a special education evaluation. The thing to remember is that a school cannot offer a medical diagnosis. Anything they find and recommend will be within the scope of educational eligibility, and if there are services offered, it will be within the district's availability. For some children, this means beginning pre-school. For others, they may attend speech, physical therapy, or social skills at the local school, but continue on with other childcare services if preschool is not indicated. This evaluation and eligibility likely will likely not be enough for additional and private therapies and services.

Meeting with the provider

Each provider will have their own process and protocol, and likely a parent interview about development and concerns will be the first step to determine next steps, which may include child observation, formal assessment of your child, and information from other raters.

Remember, your goal is to have an accurate picture of your child’s functioning. Don’t worry about preparing your child - this isn’t an achievement test that you want to have your child study and train for. Rather, you want the most representative information possible. Be sure that your child has a good night’s sleep the night before he or she meets with the assessor, with breakfast and snacks prepared. Prepare for anywhere from an hour to a half day spent with a provider - for older children, this may even include a meal break, or multiple testing days.

Prior to meeting with the provider, you will want to prepare your child for what to expect. “You are going to meet with a doctor who will want to play with you, and see how you like to play and learn. Nothing painful will happen, no shots, no dentist. Mommy or Daddy will be right in the room, or right in the waiting room.” Keep expectations cool and measured and bring a preferred toy or two from home (this helps the doctor see how your child handles new toys, and also how they transition away from loved toys!) This is not a test of your parenting or your preparedness, and this is not a reflection of you - just a snapshot of your child’s development, and a place to address any concerns in a timely manner.

Typical steps of an evaluation

-

These can be from you, your medical provider, teachers, and others

-

You could request private referrals from your medical provider or go through the local public school district

-

If you go through a private practice, call in advance to ask about availability, fees, insurance, and other relevant procedures and expectations.

-

It is common to have to wait a few months to get in.

-

Talk to and prepare your child for the testing day.

-

This can be anywhere from 2- 6 hours long or it may be broken up into multiple days.

-

Attend feedback session and receive assessment results.

What it might look like

Talia was born with some known issues - she was low birth weight, had jaundice, and had to spend a few days in the NICU. When she got home, Talia was a bit delayed in some of the motor skills - she had torticollis which was addressed in early intervention physical therapy, and she wasn’t rolling over or starting to sit which led to the physical therapists return to the home when she was 8 months old. She always responded well to intervention, but Talia’s mother knew when she was 18 months, and not yet talking, that it was time to speak up yet again. This time, Talia’s mom didn’t want to just target the issues - she thought it was time to look at the big picture, and see if there was something going on that was delaying Talia’s development. She also wanted to see if there was something more she could be doing for Talia to help her catch up, and to address any future delays.

Talia’s pediatrician agreed - she and Talia’s parents have been closely monitoring Talia’s development, and she was prepared with a list of clinical psychologists that she knows specializes in early childhood assessment for Talia’s parents at Talia’s 18 month well-child visit. She was pleased to see Talia toddling around and exploring the room, responding well to the physical therapies she had received so far, but it worried her to see Talia’s lack of eye contact, and very limited language in that visit.

-

Talia’s mom called the first two psychologists on the list right away - she left voicemails for both, and then emailed a third psychologist when she got home from the pediatrician. By the time Talia went down for her afternoon nap, the second psychologist had called her back. Talia’s mother connected with him by phone - he sounded competent, but rushed - Talia’s mom tentatively set an appointment to meet with him in two weeks and checked her email for the intake forms. The third psychologist had emailed her back. When Talia’s mother spoke to her by phone, she felt in her gut that this was the route she wanted to go - she canceled the original intake, and scheduled with the psychologist she felt more comfortable with. She was grateful to have had the options and choice. The psychologist she had scheduled with had informed her of the procedure codes she would be using for the appointments, and so Talia’s mother made note, tasking Talia’s dad with confirming that these would be covered with their health insurance prior to the appointment.

The first appointment was just Talia’s mom and dad, it took place while Talia was at her mothers day out daycare drop off. Talia’s mother was surprised that she was so emotional in the meeting, it was the first time she had actually sat down and listed all of her worries and concerns for Talia since the original issues at birth. Talia’s dad rubbed his wife’s shoulders and felt his own worries for Talia rise to the surface. He had a sister like Talia, who had always struggled to be involved in school and family life. His hope was that his daughter would have an easier and happier life than her aunt. The psychologist sent Talia’s parents home with some forms to fill out, and some to bring to the daycare as well. She also scheduled a time to observe Talia at the daycare with other kids. Talia would come into the psychologists office in two weeks for a morning of testing and observation.

Talia didn’t even know that she was being watched at daycare - to her, it was just another day playing with friends. She loved to run her hands through the gritty sand tray, and run cars and trucks along the mounds of sand. She knew adults came in and out of her classroom, but she was used to the routines and structure of her day. Her teachers had commented to her parents that she didn’t seem interested in other children, but Talia was happy enough in her own world. They provided their observations on the forms, and gave them to the psychologist following her observation of Talia.

-

The night before the evaluation day, Talia’s parents sat her down to dinner. Talia’s mother wasn’t sure how much Talia understood - she made some babble sounds like mama and dada, but it wasn’t ever really directed at her or her husband, and she usually only ever knew if Talia didn’t like something - Talia was very good at protesting! Still, she talked to Talia and narrated preparing her food, cutting up chicken, broccoli, and apples for Talia, and knowing that Talia would only eat the breading of the chicken and apples. “Tomorrow we are going to go play with someone new! She has toys and games for you, she is going to spend some time with you and I in the morning.” Talia munched away on her apple slice.

At bedtime, Talia’s mother reviewed the plan again. “Tomorrow we will wake up, eat breakfast, and then go play with a doctor at her office. She has games and toys to play with, and I will be with you the whole time.” Talia was quiet and stoic as she sat through her favorite book, clutching her stuffed bunny.

In the morning, Talia followed her routine. She seemed to notice when the car didn’t turn down the usual route to her daycare, and Talia’s mother heard a squeal of protest from the carseat in the back. “Remember, we are going to go play with some toys and games! Tomorrow we will be back at school.”

-

Talia was content to sit on her mother’s lap, clutching her bunny and waiting while in the waiting room of the psychologists office. When the waiting room door opened, Talia turned her face towards her mothers chest, appearing shy. “Hi Talia! I’m Doctor Smith! Let's go play with some of my toys - can your mommy come too?” Talia allowed herself to be carried to the room, and set on the floor. Dr. Smith sat back in a chair, an array of toys and blocks on the floor. “What should I be making her do?” Talia’s mother asked.

“Nothing at all! I’m just watching to see how she warms up and adjusts to the room. I’ll have you just sit back and watch, you don’t have to try to interact or make her do anything - I’ll specifically ask if I need you to get her attention or do something.” Talia noticed some of the toy cars and trucks on the floor - they were a lot like the trucks she loved from the sandbox at school. She scooted closer, and gingerly reached out for one.

“Talia, you found the truck!” Talia didn’t turn to the sound of her name. “Can you pass the truck to me?” Talia still didn’t turn. Dr. Smith rolled another car gently into Talia’s shoe. Talia gave a half smile towards the car, and reached out for that one as well, dropping her stuffed bunny in the process.

Talia’s mother sat back and watched as Talia warmed up. Dr. Smith alternated between taking notes on her legal pad, attempting to engage Talia or introducing her to new toys, and just sitting back and watching Talia play. Sometimes it seemed like Talia was doing well, and Talia’s mother thought “I’m just overreacting.” Other times, her heart sank, and she felt like Talia was not even hearing Dr. Smith's instructions.

“Ok mom, let's take a break!” About 45 minutes had passed, and Talia was starting to seem restless - Talia’s mother was impressed that Dr. Smith caught this before a meltdown had occurred! They convened in the waiting room for a quick snack and some cuddles with the bunny. After a short break, Dr. Smith retrieved them. This time, the testing room had a small table with a brightly colored spiral bound book propped up like an easel.

“Talia, can you sit in this blue chair?” Dr. Smith patted the small plastic chair. Talia sat compliantly. Dr. Smith engaged her with some blocks and a pattern to match. They went through some activities in the book, and Talia’s attention started to wander towards the toys on the floor. “Good idea Talia! Let's take another play break!” Dr. Smith had introduced a new set of toys in a seemingly random array.

Dr. Smith turned towards Talia’s mother. “I want to see how she handles a separation from you - would you mind stepping back out to the waiting room? We will come and get you as soon as she gets upset, if she does.” Talia seemed engaged in trying to put blocks into a container. Talia’s mother got up, and walked quietly towards the door - Talia looked up, and then returned to the task at hand.

As she closed the door, Talia’s mother heard “Oh, Mommy will be right back!” from Dr. Smith. She heard Talia slap the door and start to protest. Dr. Smith directed Talia’s attention back to some of the other toys, and Talia seemed to respond favorably - no more whines or protests.

After a few minutes, Dr. Smith and Talia came out to the waiting room hand in hand. “Time for another break! She did great - she missed you, but handled the separation well.” More snuggles were had.

Another session like that passed, with activities between Talia and Dr. Smith that alternated between what seemed like directions and instructions from Dr. Smith, and just observations. At the end of the day, Talia’s mother’s nerves were sky high. “Can you tell me anything?”

Dr. Smith answered with a reassuring smile. “You are a wonderful mother, and Talia is a special little girl. I don’t want to make her more exhausted, she’s had a long day, and I don’t want to talk about her in front of her - she picks up on everything around her, even if it seems like she isn’t listening. Why don’t you give me a call this afternoon? That will give me time to gather all of this information, and we can have a preliminary talk. I don’t want to leave you guessing or wondering.”

-

That afternoon, Talia’s mother had a phone call with Dr. Smith. “You were right to be concerned, Talia does meet diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder. She has strengths in her receptive language - she understands a lot more than she is saying, and she would really benefit from speech therapy, as well as applied behavior analysis.”

“I’ve been thinking she needs speech therapy - what is applied behavior analysis?” Talia’s mother was grateful to finally have an answer - this was not a surprise, but also a lot to take in!

“Applied behavior analysis, or ABA, is an evidence-based type of therapy based upon increasing the behaviors we want to see, helping her learn new skills, and increase her social interactions(10). I can give you a few referrals; you may also want to look on your insurance’s provider list. Let's schedule your feedback session for Talia, in a couple of weeks, so that we can go really in depth on her strengths and areas to target in intervention, and I can give you a list of recommendations. In the meantime, you can start looking into speech and ABA for her.” Dr. Smith started to offer some dates for a feedback session. Talia’s mother chose a date that aligned with her husband’s availability - she didn’t want to have to remember everything to tell him!

At the feedback session, Dr. Smith provided a report. Talia’s mother couldn’t believe that 12 pages of information could come from what she saw as just watching Talia play. Yet everything was in there that Dr. Smith talked about - Talia’s strengths in understanding, and her ability to follow sequences and routines. Her strengths in pattern recognition and matching. Areas to target, like eye contact, making sure that they had her attention when talking with her, prompting her to make sounds and giving her choices. They talked about how to talk to Talia’s daycare about her diagnosis, and how often she should be seeing the ABA and speech therapy providers. They also talked about how to tell Talia’s grandparents, aunts, and uncles about the diagnosis - what was important for them to know, and what was better to keep to the immediate family.

“How often do we need to get her tested like this?” Talia’s father asked.

“Great question - I’m glad you are thinking ahead!” Dr. Smith answered. “She’s so young now, and we caught this so early - she is going to change and grow and progress a lot in the next few years! For sure she should be evaluated before she starts school - the public school district may want to do their own evaluation, if you are putting her in public school. From there, they are required to re-evaluate her every three years - though that may consist of just looking at her old testing data and saying ‘Yep, still valid!.” It is a good idea to evaluate again around 2nd or 3rd grade if you are noticing any learning differences, like reading or math weaknesses compared to her other abilities, as this is when learning differences can be evaluated. Then again before middle school, before high school, and at least once before graduation to see if she needs any types of support as an adult.” Dr. Smith could tell that Talia’s parents were getting overwhelmed.

“One step at a time! For now, you have a beautiful, healthy, resilient toddler who needs some help with speaking and with her social skills - let's get her started there.” Dr. Smith started to gather up her documents.

“I have one more question,” Talia’s mother piped up. “Can she ever be cured of autism?”

Dr. Smith smiled. “This is a common and normal question. As of right now, no. But, we have treatment - effective, research based, safe practices. This treatment -especially as early as you are offering it to Talia - leads to significantly better outcomes(11). In some rare cases, those outcomes are so substantial that she will ‘test off’ the spectrum, and no longer meet diagnostic criteria for autism(12). Her best chance for long term outcomes is early intervention, and parents like you giving her the treatment and intervention she needs.”

Talia’s parents stood up with Dr. Smith, shaking her hand as they walked out the door. In the car they both took a moment before locking eyes. “We are going to do whatever this girl needs, right?” Talia’s dad reached for his wife’s hand.

“Already on it. We have an intake scheduled with an ABA group that specializes in language acquisition next week,” Talia’s mom squeezed her husband’s hand back.

About the author

Rachel Oppenheimer, PhD, PMH-C

Dr. Rachel Oppenheimer is a licensed psychologist and licensed specialist in school psychology, licensed to practice in both Texas and Florida. She founded Upside Therapy & Evaluation Center in 2016, working in private practice prior to that.

Resources our Experts Love

Parent Footprint with Dr. Dan Podcast↗

See specific episodes:

And Thats Okay: I’m Wired Differently with Erin Geddes

Parenting a Child with Tourette Syndrome with Michele Turk

Everything No One Tells You About Parenting a Disabled Child with Kelley Coleman

Nutritionists

•

Adult mental health

•

Couples mental health

•

Infant & child mental health

•

Sleep coaching

•

Nutritionists • Adult mental health • Couples mental health • Infant & child mental health • Sleep coaching •

When to get

expert support

Sometimes you might need more support, and that's okay! Here are times you may consider reaching out to a specialist:

If your parent gut tells you something is wrong - advocate for your child, you know best!

If your pediatrician flags a concern at a visit

If your teacher or daycare provider mentions a concern

If you are wondering if everything is developing on track

-

Okoye, C., Obialo-Ibeawuchi, C. M., Obajeun, O., Sarwar, S., Tawfik, C., Waleed, M. S., Wasim, A. U., Mohamoud, I., Afolayan, A. Y., & Mbaezue, R. (2023). Early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: A review and analysis of the risks and benefits. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.43226

Campbell, J. M., Ogletree, B., Rose, A., & Price, J. (2020). Interdisciplinary evaluation of autism spectrum disorder. Interprofessional Care Coordination for Pediatric Autism Spectrum Disorder, 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46295-6_5

Kamp-Becker, I., Tauscher, J., Wolff, N., Küpper, C., Poustka, L., Roepke, S., Roessner, V., Heider, D., & Stroth, S. (2021). Is the combination of Ados and adi-R necessary to classify ASD? rethinking the “Gold standard” in diagnosing ASD. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.727308

Wisner-Carlson, R., Pekrul, S.R., Flis, T., & Schloesser, R. (2020). Autism spectrum disorder across the lifespan: Part I. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 43(4), i. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0193-953x(20)30062-9

Individuals with disabilities education act (IDEA). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2024, July 24). https://sites.ed.gov/idea/

Russell G., Norwich B. (2012) Dilemmas, diagnosis and de-stigmatization: Parental perspectives on the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 17(2), 229-245. doi:10.1177/1359104510365203

Randall, M., Egberts, K. J., Samtani, A., Scholten, R. J., Hooft, L., Livingstone, N., Sterling-Levis, K., Woolfenden, S., & Williams, K. (2018). Diagnostic tests for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in preschool children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd009044.pub2

McLeod, B. D., Doss, A. J., & Ollendick, T. H. (2013). Diagnostic and behavioral assessment in children and adolescents: A clinical guide. Guilford Press.

Clark, M. L., Vinen, Z., Barbaro, J., & Dissanayake, C. (2017). School age outcomes of children diagnosed early and later with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3279-x

Cleveland Clinic (2024, May 1). Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/25197-applied-behavior-analysis

Saral, D., Olcay, S., & Ozturk, H. (2022). Autism spectrum disorder: When there is no cure, there are countless of treatments. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(12), 4901–4916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05745-2

Woolfenden, S., Sarkozy, V., Ridley, G., & Williams, K. (2012). A systematic review of the diagnostic stability of autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 345-354